Summary

Peer advice and advisory committees are the principal instruments used by the benefactor,

usually called the Program Officer (PO), who handles the decision making process for

research grants. His experiences have neither been described nor investigated. An attempt

is made here to fill this gap. Consideration is given to the structure and operation of panels,

contradictions in peer review and the role of the defense.

POs in general.

Most scientists have mixed feelings about the fellow I would like to put in focus to-day. It

seems the appropriate occasion to do so, because I guess, that it is the character that Jaap

Kistemaker will be glad to miss in the near future.

My subject is the program officer, PO, in a government research agency, also referred to

as a research administrator. He administers or manages science at a distance. This reminds me of

my old Leiden professor of philosophy, who visibly being of a certain religeous denomination,

kept on doubting if such 'actio' could really exist. A PO is a person, who sits back at a desk

in some office building, in most countries - but not in Holland - in the nation's Capital, far away

from the bench, where scientists try to do their jobs. His function is to decide to which person,

group or laboratory the always scarce funds for research will flow and to whom they will not. In

The Netherlands for many centuries people did not believe very much in the wisdom of power vested

in individuals. (Neither did they believe in Capitals, I might add.) Throughout the state and in

many other sectors of society the formal decision taking is and has always been done by committees,

boards, cabinets, or whatever names these bodies may carry.

John de Wit in the time of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces was considered by most

foreign heads of state to be the nation's chief. He was not. He was the servant of the state, its

true secretary. He had about five assistants to help him. But he was not allowed to pick and to

appoint these men by himself.

Our queen, although entitled by the constitution to appoint and to dismiss cabinet ministers

as she pleases, would never dare to dream of doing so.

In line with this good old tradition we have no program directors as they exist in the USA. We

rather have program officers, who serve as secretaries to committees or boards and whose job it is

to formulate the decisions drawn up by these bodies. Now I suppose you have all heard about Alvin

Weinberg's allusion to the inaptness of committees to do any good. He referred to a camel as being

a horse drawn by a committee. This he may have observed, but I dare say that his committee must have

had a rather poor secretary.

Whether in realty the system, where the secretary only formulates the decisions, differs much

as to the quality of the policy it produces, from the system, where the PO decides after having

consulted an advisory group or panel, remains to be seen. Anyhow for a country in which it is virtually

impossible to sack any crazy or senile tending official, I think the committee rule system to be

safer. Let us keep it that way.

POs come in variety. Some can always cover a neighbouring field as well. Those are the empire builders

and in extreme cases they may stir up a lot of trouble. On the other hand there are the seclusionists

for whom anything new falls for this reason or another just outside their limits of responsibility. No

troublemakers for sure, but in their extremes, herders of very dull and unimaginative science. The

golden course is somewhere in between.

The selection of a good PO is of utmost importance for the well being of the specialty, he is

dealing with. This I found a generally recognized concept in the USA, where the PO takes the decisions.

In Holland, however, where the power is with the committee, this requirement is often overlooked,

because he is 'only' the secretary and his function is 'just' to carry out, what the committee in its

wisdom decides. This point of view is erroneous. It may lead to ineffectiveneness of committees, even

of those that are made up from the best experts a nation has. Sometimes the flaw is compensated by a

good chairman. But then the chairman must also assume the role of the secretary. In busy committees

this means his farewell to the research front.

POs are a privileged set. They communicate daily with the best experts the country posesses.

Their frame of reference is the nation's top. On the other hand they write the grant awarding or

grant refusing letters. This dualistic role may lead to overestimation of the own position. Therefore,

feelings of humbleness and a certain firmness are to be balanced carefully.

A good PO splits his time between desk work, contacts with the research field and contacts with

the sources from which the money and directives come. He should be sensitive to new developments in

science as well to new trends in the government's science requirements and expectations. It is his

job to match the demands of the scientific world as to organizational matters with those of the

financial superstructure. He mans the first bastion to shield the scientific community. He should

always be alert to protect against the natural tendency of the government bureaucracy to uniformise,

and regulate and to stifle the free opportunities that are necessary for a vigorous and healthy

development of the research enterprise.

I want to emphasize once more the danger of underestimation the quality of the PO. Recently we

have seen a rather unusual growth in the number of PO-type government appointments in different branches

of the administration. In The Netherlands these positions were filled with young scientists arriving

fresh from the universities. They often lack the necessary knowledge of the structure of the scientific

community. And they try as soon as they can to set up their own advisory structure. This is apparantly

a simple task, since most scientists are always on the look-out for new resources for their work.

They are easily persuaded to serve on this or that committee, certainly if it is appointed by the

minister. Such advisory panels usually suffer from - unintentional - serious omissions. Secondly

the new body lacks coherence and experience, present in older, existing organizations. Therefore it is

easily guided by its young secretary - who supposedly knows, what the minister wants - rather

than the other way round, which is the underlying principle of an advisory group. The practice often leads

to interesting looking new initiatives, which are well received by parliament. But for those, whose

memory is slightly better than the stories in yesterday's newspaper, the outcome is often a

disappointment.

A PO should always strive for balanced scientific advice. He should follow, not lead! The time to

lead may come later, when he knows the field thoroughly. When he knows the options and the criticisms.

Only then he becomes fit to help make decisions, which through lack of courage, or irresoluteness might

otherwise not be taken. A PO, who starts out knowing what has to be done and how, should be treated with

utmost distrust especially if he is young and if his main arguments can be read in any newspaper. In

the USA I was repeatedly told that even POs who had been full professors in their fields and who became

NSF program directors, were not to be regarded as specialists any longer. This is of course more true for

people who have never, or have only incidentally reached the research front.

Beware for good 'administrators'

Although a PO is supposed to administer science, he should not be too good an administrator. This may

sound odd, but there is a good reason for the statement. Often sience requires fast decisions and flexibility.

These characteristics are absent in big administrative systems. Therefore the PO should maintain a healthy

personal dislike for the regulatory disease. I want to give an example.

Consider the case of a famous professor, who applies for a grant. The application is received by the PO,

who reads the accompanying letter. It states that the principal investigator, the PI, happens to have

met a brilliant young physicist, especially suited for the job. Since the man is also considering other offers,

please decide immediately! The PO smiles about the professor's naivety. He starts the advisory procedure.

After some 6 months, he informs the PI gladly that the grant is awarded. And now the need for a not so

good administrator becomes obvious. Because our PO soon finds out that a student of electrical engineering is

appointed and the money allocated for instruments has to be used in part for travel to Yorktown Heights, whereas

rather than solid expendables an amount of software has been ordered. In the first article published the only words

that can be traced to having something to do with the research grant, are in the 'acknowledgement'.

If he were a real administrator, he would raise hell. If he is a good PO, he picks up the phone, has

himself convinced by the PI that this was the best course of action and writes OK on all bills and letters

of appointment sent up to him with big question marks from the personnel and finance departments. He knows:

- The PI is not mad;

- If he is, the next application with its attached progress report will surely be killed by the

cleverly selected peers in his advisory apparatus.

An attempt to have the modifications approved by an inbetween advisory procedure might easily lead to a

subsequent request to appoint a mathematician instead of the electrical engineer and to supplement the funds

for equipment with a handsome amount, because now a full size computer is needed.

POs should develop a skill for such occurrences. They are there to cover up, to help rules and

regulations adapt and in general to stimulate not to frustrate scientists. They are there to be fooled,

to help to enable exceptions to be made. And they should - that is the code of honour of their trade -

stand up jointly and defend an unfortunate colleague, if he is accused of arbitrariness, prejudice, or being an

inapt administrator. That is, if he did so in order to help an odd bird of a scientist, who tried to do something

in a different way.

After this plea, unfortunately based on practical rather than philisophical wisdom, I would like to dwell

for some time on the role of committees, boards etc., which constitute the policy building for science and

technology.

Committees

Before I raise doubts, let me state clearly: we need committees. And we need them not only for

cosmetic reasons, but also for organization and for efficiency, but...

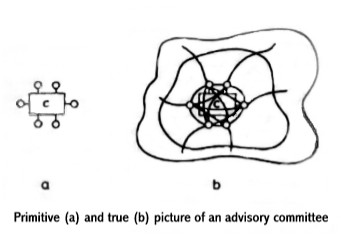

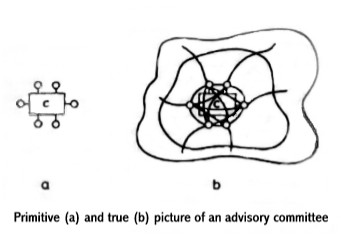

Let me again approach the problem in a general way. We need scientific advice and proper decisions. The

first thing that comes to mind is: Let's have a committee. The aims and objects of this committee we may

call the charge: c. A number of individuals preferably renowned for their skills in the particular

field are approached with respect to the charge and appointed. The idea is, that the charge will unite

them and focus them with neglect of all other ties, figure (a). But of course, this picture is hopelessly

incorrect. In fact the charge constitutes but a minor and insignificant part of the lives of these

individuals. Most of them knew each other long before the charge was there. They have their mutual ties

and interests and they have numerous ties and charges with the surrounding community. So a more appropriate

picture of the committee is figure (b). Here we see that our committee is almost non-existent. (Except for

its full time secretary to whom the committee is a substantial part of his life.) Committee members have

usually no interest to allienate their fellows, because there are so many common and long lasting interests.

They will virtually forget about the charge. And they will act socially.

Think of this when you sit in on a committee. It will help you endure it. My description implies a lot,

but not what the instigators had in mind. If things don't work out so well, it is usually the

composition that is blamed. But that is mostly a mistake. Usually these panels encompass all the talent

in a special field that the country has. In the physics research branch, FOM, for instance they include

all leading specialists in that discipline. There could be no more qualified set of people to establish

priorities. Actually that was not always the case. The mechanism described before, interferes. Most members

of such committees will not speak out freely. The few that try, may easily become isolated; or the net result

is a common resentment against that what was stated so bluntly. If a proposal is discussed, it turns out to

be very important, who speaks first. If he praises it, the chances are low that this opinion will be

averted. The same happens, when the first speaker shows himself critical. In the USA this phenomonon is

called 'Senatorial Courtesy'. It is a well known feature in the study of human behaviour. We should not forget

that, although we are dealing with scientists, we are first and foremost dealing with humans. Fortunately,

I may say.

It is here, that the proper PO can play an important role. With due consideration for the impressive

knowledge and skills of the top experts, he should manoeuvre, negotiate, persuade and persist in trying

to draw out the best of what they allow to become known. If they say things in private that they are not

willing to repeat in public, schemes and procedures should be developed to depersonalize data and opinions.

Comments should be made debatable without revealing the source and so on. By doing so, it is possible to

approach the essence of the committee idea: Top experts exchanging and freely forming opinions, while

being totally devoted to nothing but the charge of the committee.

Mail review

Many research agencies around the world acquire peer advice by mail. Agencies send applications for review

to independent advisors, who are supposed to fully understand the proposals. They are asked to comment and

even to grade these documents, as if they were student's termpapers. This method is also used by FOM and

STW in various programs. In many cases the reviewers are foreigners and the applications and the advice

are written in English. This method came under discussion as a result of a COSPUP study by Cole, Cole and

Simon,

published in Science in 19812. They studied decisions made by NSF on 50 grant applications

in solid state physics, 50 in chemical dynamics and 50 in economics. In order to check whether program

directors predetermined their decisions by a biased selection of reviewers, they selected with the aid

of a panel composed mainly of NAS-members a number of new referees. And they asked them to judge the

proposals in the same way as the original reviewers were asked. The outcome was compared to that of the

original advice. Their conclusion was that 25% of the projects would have received a reversed decision

if other referees had been selected by the program director. In the sample half the proposals received

an award, so a random choice would have produced a 50% reversal rate.

The article triggered a lively discussion. Some of it reached the public at large. Cole et al.

emphasized in a later comment that half of the decisions were based on consensus in the reviewer

community and half on the luck of the reviewer draw, which means that the current peer review system

is 'decidedly superior to one based on random selection'3. But other critics maintained that

even that conclusion is too weak. Humphreys e.g. noted that grant proposals received by NSF are far

from a random selection of all potential research proposals, due to self-selection by the

applicants. They restrain themselves, because they know that their proposals will be reviewed by

their peers4. He argues

that the 150 proposals studied must be closer to one another in quality - with all the risk of small

number permutations - than a true random sample would be. We have evidence in FOM to support Humphreys'

assumption. The variation in quality of the proposals in the working communities - where the

program is systhematic reviewed by what the participants recognize to be their peers - is much less

than in the 'Beleidsruimte', a general program, that is perceived as being closer to a random sample.

PO influence

Cole et al. disregard the role of the PO in the decision process. In a previous observation they

found a good correlation between grant decisions and peer review ratings. So they used in the study

mentioned here the average ratings of a peer group. A shift from below average to above average in

their view means a shift from refusal to award. It may well be, that in some NSF-programs the

directors favour the easy way to avoid arguments. And that they base their decisions on average

ratings only. But that was certainly not the case in those NSF-programs with which I was familiar at

that time. Among those I count the solid state physics program. Let me give two examples.

The research method of Cole et al. is too cumbersome. There is no need for a second group of

reviewers. One could simply look at the consensus and dissension within the original reviewers group.

Consider a proposal in theoretical physics. The prevailing criterion in that subfield is, as

everyone knows, the quality of the people involved and - since the junior-staf is not yet known -

predominantly the quality of the PI himself. In this case the proposal is sent to four reviewers.

Three of them applaud the proposal on grounds of past performance and they rate it excellent. The ,

fourth, however, comments that his judgement (= about average) stems from the fact, that the PI is

presently in the hospital and he will most likely never return to his lab. His confidence in the

acting project leader is not very high. The NSF program director whom I met, had no hesistation about what to

decide. Although the judgement of the four was certainly above average, the proposal was turned

down.

An analogue situation may arise on other criteria. Take the following example of an

experimental proposal. Some referees made serious objections to the allowance of a grant, because

the small laboratory from which it originated, did not dispose of some pieces of equipment, which

were thought to be essential for the conduct of the experiment. One referee, who rated the

proposal 'excellent', remarked that he admired so much the clever way in which the group made use

of precisely that kind of equipment, which was standing idle in a nearby industrial lab. The

average rating by the peers was about average, not high enough at the time. But the program

officer nevertheless and quite rightly, I think, awarded the grant. These occurrences are overlooked

in the research of the Coles and Simon.

This interference by a PO on some of the decisions may completely upset the statistics

on which the investigators based their conclusions. The FOM and STW archives are loaded with material to

support this statement.

In the same archives one can find data about the judgement of 'juries'. That are groups of people

that once assume the role of a PO. (In this way the organizations avoid vesting power in individuals, see

above.) It would allow one to study the behaviour of different "POs", who are looking

at the same proposal and the same peer advice. Let us hope that some science of science student at one

time will reveal the wealth of empirical policy material which is readily available for harvesting.

There is no need even to bother people with questionnaires or interviews.

In a brief scan of the archives of FOM and STW, we found so many examples, that we dare to state:

POs (jury members) do not simply count the pros and cons in referee reports, neither do they just average

referee's judgements. They do look at the contents of the advice and they pay due attention to the

arguments.

We also state: The COSPUP study shows a serious deficiency by overlooking the role of the PO in the

procedure. It is amazing that this aspect has not been observed. We estimate that it would have

been cheap and easy to complete the experiment with a PO-simulation.

Applicant's defense

There is a fundamental difference between most NSF-review and that practised by FOM or STW. The latter two

provide for an opportunity for the applicant to defend himself5. The defense is in some cases

of definite importance. We discovered even some generalities there. One is: if the peer statements, apart

from some general polite comments, are in majority sceptical, but not specific and if the defense

by the PI is concise, clear, to the point and convincing, juries (series of pseudo "POs") tend

to grade the proposal higher than when it was given to them without accompanying peer review and defense! In

some cases the effect was astonishing. The proposal rose to the top in a certain set of competing proposals.

It is amazing that there are still many government research agencies that do not offer the applicants this

right of defense. Since Justinianus codified the Roman Law it has been good practice in all civilized

countries to allow the defendend his say before a verdict is given6.

General conclusion

I hope I succeeded to convince you, that POs are important, both when they act as directors - the US case -

and when they act as secretaries. More attention should be paid to their selection than is currently the case

in some organizations in The Netherlands. At least a longer apprenticeship should be allowed for.

References

- Slightly revised version of a contribution to the seminar in honour of Prof.dr. J. Kistemaker's

65th birthday. Published in: Management of Science, relation to industrial and national needs,

April 23, 1982, North Holland.

- S. Cole, J.R. Cole and G.A. Simon: Chance and consensus in peer review, Science 214(1981)

881.

- S. Cole et al., Science 215(1982)346/8.

- L.G. Humphreys, Science 215(1982)344.

- Recently I learnt that 'applicants defense' is now becoming more a part of the decision process

in the US than it used to be. That is not too early, I would say. We were some 30 years ahead.

- C. le Pair, Physics Today (1976)13.